Images of the Canadian Arctic

1974-1976

by Don H. Meredith

In 1974, after completing my field and course work for my Ph.D in Zoology at the University of Alberta, I took employment with Renewable Resources Consulting Services Ltd., to join a team of biologists studying the distribution and behavior of caribou and muskoxen in relation to the building of a proposed gas pipeline (Polar Gas Project*) in the High Arctic of Canada.

That first year, we mainly flew aerial surveys to determine the distributions of the two species. The surveys were based out of Resolute (Qausuittuq) on Cornwallis Island in the High Arctic Archipelago. We also set out some camps to investigate caribou habitat.

In 1975, I spent six weeks in a camp on the Boothia Peninsula to determine the migration patterns and movement to calving areas for Peary caribou. David Nanook, an Inuk from Spence Bay (Taloyoak), was my assistant. I learned many things from David about the Arctic, the culture of his people, and how to live and survive in this unforgiving environment.

The summer of 1976 found me once again in the Arctic, this time working for another biological consulting firm, LGL Limited, in relation to protecting a research camp from marauding polar bears. Enroute to the camp, I spent some time with LGL's marine biology crew and visited the graves of the first casualties of the ill-fated Franklin Expedition (1845-48).

The following are just some of the images from those summers. They were scanned from 35 mm film slides:

Canadian Arctic—1974

Slide 1 — Resolute from the air, May 1974

Polar Gas Project

In the late 1960s and early ‘70s, petroleum and natural gas production peaked in North America and other parts of the world. Companies began exploring far-flung regions to look for new sources. As a result, an estimated 450 billion cubic metres (16 trillion cubic feet) of natural gas reserves were found in the High Arctic Islands in Canada. The Polar Gas Project was formed in 1972 to determine how to move that gas to southern markets. The project was a consortium of companies, including TransCanada Pipelines, Panarctic Oils, Tenneco Oil of Canada, Petro-Canada, and the Ontario Energy Corporation. Pipeline routes were proposed from the islands to Montreal where it would connect with other gas pipelines.

Work began in 1974 on the feasibility of the routes, including assessing the potential environmental impact on the flora and fauna, as well as the impact on Inuit hunting and fishing. Several biological consulting firms were hired to look at the plants, mammals, birds, fisheries and marine environment along a corridor from King Christian and Melville Islands through Cornwallis Island, across Barrow Strait to either Somerset or Prince of Wales Islands, and then on to the Boothia Peninsula (mainland North America) and south.

Although the environmental impact of the pipeline would be significant, the engineering required to lay pipe was substantial. The pipeline would have to pass over permafrost and under large stretches of ice-covered ocean. The ocean alone posed many problems, including how to get the pipe from land to undersea while passing through several metres of sea ice that rises and falls with the tide, and moves with the currents, scouring the coasts.

All of those concerns soon became academic. In the early 1980s, much cheaper natural gas was discovered in the south and the project was abandoned. The natural gas reserves are still there but current thinking is that if and when they are needed, the gas would be liquified in the Arctic and shipped out by tanker, as a result of the opening of the sea ice by global warming.

Although I had prepared myself for the trip to the High Arctic—read about its history, animals and environment, I had not expected the environmental and cultural shock I felt when I stepped off the Pacific Western Airlines 737 in Resolute Bay after a long flight from Edmonton. First, one doesn't realize just how big Canada is and how much of that size is the Arctic until you get on a plane and make the journey. In those days, it took most of a day to fly from Edmonton to Resolute, including a stop at Cambridge Bay. Second, the completely barren landscape above the Arctic Circle, totally devoid of trees and shrubs, takes some getting used to. There's little shelter from the wind and cold and no wood for a fire. Third, we were working out of a small village that was totally focused on servicing the petroleum industry. All day and all night, Hercules (C-130) aircraft would take off about every 20 minutes with loads of supplies and fuel for the petroleum exploration camps in the surrounding archipelago.

Slide 2 — Canada is a big country (second only to Russia in size) and the Arctic is a big portion of the country. Resolute is 2500 kilometres (1550 miles) from Edmonton. (Google Map © 2018)

Slide 3 — Our chief airplane used to do our aerial surveys was the Dornier Do 28 (here, CF-HBD shown on skis/wheels at the Resolute Bay Airport). It's unique design of high wings without struts, large viewing windows and twin engines, combined with its STOL (Short Take-Off and Landing) capabilities, made it an ideal Arctic survey aircraft.

Slide 4 — Inside the cockpit of the Dornier. Left to right, pilot (and part owner of Contact Airways) Jack Bergeron and biologist Dave Wooley (now Hugh Wollis). The lead biologist for the survey sat in the navigator's seat to the right of the pilot and ensured we flew along the survey transects.

Slide 5 — Bob Wooley and Lyle Dorey (l-r) in the rear observer positions in the Dornier. Yes, Lyle was cold in this photo. For safety reasons, the airplane heaters were not turned on until it was airborne. Once airborne, the cabin heated up quickly.

Slide 6 — The Boothia Peninsula, northernmost point in continental North America. Arctic landscapes are stark and finding caribou or muskoxen to count was challenging.

Slide 7 — Bull Peary caribou on Cornwallis Island. You can see how easily these animals blend into their environment, making them difficult to see and count from the air.

Slide 8 — Muskoxen were much easier to see from the air, but they were few and far between.

Slide 9 — A closer look at a muskox on Cornwallis Island.

Slide 10 — View from the air of the Inuit village of Spence Bay (now Taloyoak) on the Boothia Peninsula. The large cleared area was the construction site of a new school being built in 1974 by Poole Construction Ltd. (now PCL) of Edmonton. Spence Bay was the base we used to fly surveys in the southern High Arctic, and we stayed at the Poole Construction camp.

Slide 11 — Refueling the Dornier on the sea-ice landing strip at Spence Bay. Fuel was pumped by hand from 45 Imp. gallon (205 litre) drums. Pilot Jack Bergeron oversees from the wing. Lorne Fisher pumps the fuel while Dave Wooley looks on. Note nursing station in background.

Slide 12 — A polar bear on the sea ice near the Grinnell Peninsula, NW Devon Island.

Slide 13 — Refueling from a fuel cache placed on the Grinnell Peninsula, Devon Island. The caches were placed earlier that year in anticipation of the surveys. We flew surveys covering the islands from Ellesmere Island south to the Boothia Peninsula.

Slide 14 — The Midnight Sun from the air over Lancaster Sound. Because the weather could be problematic and the seasons so short, we took advantage of the continuous daylight and often flew through the early hours of the morning.

Slide 15 — In the spring (when the sun begins to dominate the sky), seals pull themselves up on the ice (gathering near cracks for easy escape into the water) to sleep in the sun and live off the fat they have accumulated over the winter. It is also a prime time for polar bears to hunt them. Note the bloody spot along the crack in the upper portion of the photograph.

Slide 16 — We didn't spend all the time flying surveys. Later in the summer we set out camps to investigate caribou and muskox habitat. Here is our camp at Sanagak Lake on the Boothia Peninsula.

Slide 17 — Twin Otters, out of Resolute Bay, were used to set out our camps.

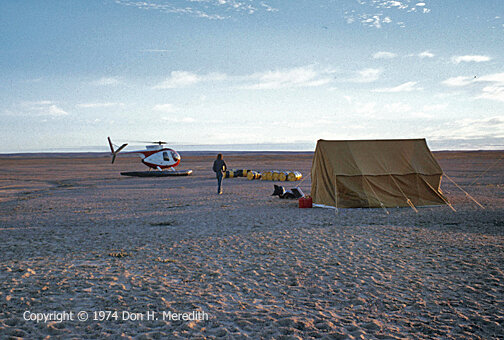

Slide 18 — A helicopter took us to survey sites.

Slide 19 — A bull Peary caribou near our camp on Somerset Island.

Slide 21 — Arctic fox would often enter our camps, seemingly unafraid of our presence. They are about the size of a large house cat and looked for whatever food we might have exposed. We had to be careful around them because they were known to carry rabies.

Slide 22 — A pair of Willow Ptarmigan. A very hardy bird that stays in the Arctic all year-round. They depend on their camouflage to protect them from predators.

Canadian Arctic—1975

Slide 23 — My Inuk assistant was David Nanook of Spence Bay. His job, besides guiding me to where he knew caribou calving grounds to be, was to make sure this Kabloona didn't kill himself. I learned a lot from him. Here he stands with the skull of a bull caribou we found near camp.

April of 1975 found me back in the High Arctic again with the Renewable Resources crew. We had learned a lot in the first season. We had a good idea where the caribou and muskoxen were, at least in the summer, and we had a good idea what the habitat looked like and how to assess it. Aerial surveys were to continue but we also needed to get more on-the-ground information about the quality of habitat and the location of calving grounds.

Lindsay Rackette and I set out camps on Prince of Wales Island (Lindsay) and the Boothia Peninsula (me). We prepared all winter for these camps, learning the proper way to drive snowmobiles and building a pair of komatiks or Inuit sledges. We built them in Lindsay's basement using Inuit techniques—no nails or screws, all held together with rope. It was quite an experience and our Inuk assistants approved our work.

Slide 24 — David Nanook (left) and I at our Wrottesley River Valley Camp on the Boothia Peninsula.

Slide 25 — After setting out our camp, I had to get oriented, so David and I drove our snowmobiles south to the head of the valley. This allowed me to get perspective on the valley and David could show me where we needed to go to find caribou.

Slide 26 — Looking west from our camp at the valley edges. We tried to drive our snowmobiles up that valley to see the coast but they bogged down in some very thick but deep snow that had accumulated there over the winter. The valley however was covered in much harder and denser snow that was wind-blown.

Slide 27 — Our camp was laid out to keep polar bears away from our sleeping tent (left). We cooked and lived in the frame tent (centre) with the oil stove. Our meat cache is barely visible in the distance behind the sleeping tent. If a bear would come to camp, it would be attracted to the meat cache or the cooking tent. Luckily no bear ever came during our stay there.

Slide 28 — Every once in a while, the Dornier would pay us a visit and bring us supplies and mail.

Slide 29 — Weather in the Arctic is always an issue. There are no trees or shrubs to break the wind. Hence our main tent had an interior frame and two layers of canvas.

Slide 30 — This is Pukaq, the crystalization of snow near the soil, where heat from the earth changes the crystals. If thick enough, this layer can prevent animals from smelling the plants (food) underneath.

The Inuit people have several names for snow based on the different types found in the Arctic. This is not hard to understand if your success at finding food and travelling across the landscape depended on your knowledge of the snow types. In our study we examined the snow types caribou use to travel and dig through to feed, using the Inuit name for each.

The following are just two examples of the types of snow we encountered.

Slide 32 — Mapsuq close up. Note the old snowmobile tracks revealed below the fresher layer of snow.

Slide 31 — Mapsuq only appears in the spring when warm winds cut into the dense snow pack and carve out these blocks from the various layers. Mapsuq is very hard, difficult to travel over and generally avoided where possible.

Slide 33 — In the deep cold, ice fractures easily with the blow of an axe.

One thing I enjoy about camping is that it forces you to deal with the esssentials from which modern life shields us, such as: fuel, food, water. In our arctic camp, food and fuel were shipped in with us. In other words, modern society (through the oil companies that were financing our study) had covered those essentials. However, water was another issue. Even though it was April-May, streams and lakes were still covered with very thick ice. With temperatures plummeting to -20C at night, free-flowing water was not available. So, David showed me how to obtain drinking water from lake ice.

Slide 34 — Splitting the ice in one direction, followed by splitting it at 90 degrees, and soon you have an ice block that is easily levered out.

Slide 35 — Soon we had several blocks of ice we loaded on the komatik and hauled to camp. We melted it on our cook stove and stored the remainder in a snowbank. In those days, it would have been hard to find more pristine water than what we had there.

Slide 36 — David starting to cut the snow blocks. He used both his traditional snow knife, stuck in the snow on the left, and the modern snow knife/saw in our arctic survival kit (supplied by Polar Gas).

As the season progressed and we documented much of the caribou activity in the Wrottesley Valley, David told me of an area along the northern Boothia Peninsula that had a calving ground. This area was about a day's trip away by snowmobile. As we packed our gear, David told me not to pack the sleeping tent as he was going to build an igloo in which we'd sleep and cook. At this point in our time together I had learned to trust his judgement and said OK, that's what we'll do. Still, I had a bit of apprehension about whether we were going to have shelter for the night.

We drove our skidoos down the Wrottesley River Valley to Wrottesley Inlet, where we saw a polar bear and her two cubs. After we drove to Pattison Harbor and then up to Amituryouak Lake, we set about finding a place to set up camp. We found a lake where David informed me there should be sufficient snow of the type suitable for building a snow house or igloo. The snow (illusaq) is found on the leeward side of a lake where it has been blown across the lake, the individual snowflakes busted down to small crystals packed together by the wind and gravity to form a very dense snow pack.

David took his traditional ice knife and probed the snow until he found a section of the pack that would provide snow blocks of sufficient quantity and size

Slide 37 — David taking blocks of snow out of the pack. An igloo is built down as well as up.

Slide 38 — An igloo is built in a continuous row of blocks that spirals up. Each block is shaped to fit the previous block and the one below. Note David's traditional parka made from caribou hide with the hair side in. The parka is a pullover. No buttons or zippers. Caribou hide is very warm. Indeed, we slept in the tent or igloo in modern sleeping bags on top of layers of caribou hide that David provided. The hide insulated us from the cold coming from the ground.

Slide 39 — David lifting a block up into the spiral.

Slide 40 — David shaping the blocks to fit the one below and the one before.

Slide 41 — David finished as the sun set. Note the flat top of the igloo. David did not dome over the top in the traditional manner because 1) it was late spring and temperatures were comparatively mild and 2) we would be cooking inside with a gas stove, creating much heat and threatening the collapse of a snow block ceiling. So, to top off the igloo we tied a canvas tarp on top to act as a roof.

Slide 42 - Sunset as we entered the short spring night.

Slide 43 — At about 2 a.m. that night, David aroused me from a deep sleep to say we had to get up because the wind had blown the tarp off the igloo. As snow fell through the open hole, we scrambled to get our clothes on and exit the igloo to find the tarp hanging on by only one rope. We quickly gathered up the tarp and with some effort pulled it over the igloo and tied it down to just about anything that would hold it down, including fuel drums and snowmobiles.

Slide 44 — We did find the calving ground and I was able to record mothers with their calves.

Canadian Arctic—1976

The summer of 1976 found me once again in the Arctic, this time working for LGL Ltd., another biological consulting firm. They hired me for work in the Rocky Mountain foothills of Alberta. However, on this particular assignment, I was going to help a research camp in the Very High Arctic protect itself against polar bears. The company had approached LGL about somebody that could help them out with some problems they were having with the bears, and I had the most arctic experience in camps, so I was drafted to go.

If you are an impatient person, the Arctic is not for you. Transportation is always an issue. You often spend hours and sometimes days waiting for air transport to show up, often delayed because of weather or mechanical issues. My arrival at Resolute Bay was in an old DC-3 that had been chartered by a consortium of companies because of a Pacfic Western Airlines strike that had crippled air traffic to the North. The cargo aircraft was packed with supplies, and people needing to get North. The flight from Calgary took most of a 24-hour day with many refueling stops.

Slide 45 — A DC-3 at Resolute Bay, not unlike the one I flew from Calgary to Resolute during the PWA strike in 1976.

Slide 46 — LGL hired this helicopter to take the marine crew to locations on the sea ice along Lancaster Sound.

Upon arrival at Resolute Bay, I learned that the helicopter the company had hired to take me and some supplies north to the research camp had been delayed by mechanical issues in Edmonton and would take a few days to get to Resolute. It so happened that LGL's Toronto office had a team of marine biologists in Resolute, studying the marine biology of the waters that would be crossed by the proposed Polar Gas Pipeline. I tagged up with the crew and helped them with their study while I waited for my chopper.

Slide 47 — We set nets in the water along the edge of the ice to catch shrimp and fish, and determine the species and numbers.

Slide 48 — We used Zodiac inflatable boats to set nets in other locations.

Slide 49 — Open water can be deceiving and dangerous in Arctic waters. The wind can quickly push the ice floes together and form barriers to your return. So, we had to keep a lookout for what the wind and ice floes were doing.

Slide 50 — Not all wildlife were in the water. Here a bearded seal is resting on an ice floe.

Slide 51 — In 1976, we visited Beechey Island as part of our marine surveys. Although I had read about the Franklin expedition before I came to the Arctic, I had forgotten the significance of this island to Canadian history. Upon seeing these graves, we all soon realized what we had stumbled across.

Franklin Expedition—Beechey Island

In 1848, Sir John Franklin's third Arctic expedition, in search of the mythical Northwest Passage, ended in tragedy — all 129 men and two ships (HMS Erebus and Terror) were lost. Many expeditions from both Britain and the U.S. were launched to find these men and their ships, resulting in the exploration of much of the Arctic. Franklin's first winter camp (1845-46) was found in 1850 on Beechey Island (about 80 km east of present-day Resolute Bay), along with the graves of three men.

I was surprised there wasn't some sort of monument or permanent marker commemorating this Canadian historical site. It turned out there was at least one other grave there, that of Thomas Morgan who died on the island in 1854 as part of one of the search expeditions to find Franklin. However, his grave was not marked at the time we were there.

Slide 52 — I later learned from Frozen in Time (1987, Owen Beattie and John Geiger) the names of the occupants of the graves. From left to right, the graves and original markers of Royal Marine Private William Braine and Able Seaman John Hartnell both of HMS Erebus, and Petty Officer John Torrington of HMS Terror.

Slide 53 — The grave marker of 25-year-old John Hartnell, who died on January 4, 1846. His was one of the graves exhumed by Owen Beattie in 1984 to determine the sailors' cause of death. Beattie concluded that pneumonia and lead poisoning may have played a role in these deaths. However, subsequent studies determined that although lead levels were high in these men (as they were for people back home in England), they were likely not the main cause of death.

The writing on the markers looked to us like it had been burned into the wood. However, I later learned that the black in the letters cut into the wood was actually black paint that had been applied to them in 1904 to make them easier to read. Many years of arctic winds and abrasive snow had eroded the wood around the letters, leaving what remained of them raised above the surrounding surface, as if embossed.

These slowly deteriorating markers were replaced in the 1990s with bronze memorials. The original markers are stored at the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre in Yellowknife, NWT. In 1993, Beechey Island was designated a National Historic Site of Canada.

In 2014 a Parks Canada search team found the wreck of the Erebus in Queen Maude Gulf. The wreck of the Terror was found in 2016 south of King William Island by the Arctic Research Foundation. What happened to Franklin and the remainder of his crew remains the subject of much speculation and research. The mystery continues...

Slide 54 — Resolute Bay in 1976 from a helicopter.

Epilogue

When my helicopter from Edmonton finally arrived in Resolute, I bid farewell to my LGL colleagues and boarded the chopper along with some supplies and mail for the research camp on Ellef Ringnes Island, about 500 km northwest of Resolute Bay. Upon arrival at the camp, I met the safety officer, who showed me the problems they were having with polar bears wandering into the camp. No one had been hurt but the people in the camp were rightly concerned. The camp had largely followed common sense, making sure no food or other attractants were left outside the trailers and checking for bears before leaving a building in groups of two or more. I suggested some other things to do, like enforcing not bringing food into sleeping quarters and discouraging bears from entering the camp in the first place by keeping watch and having noise makers at the ready (sometimes that works and sometimes it doesn't). I also gave a presentation about the bears to the camp staff so they would understand the animal a little bit better. After all, we (humans) were the intruders here. As far as the polar bears were concerned, they ruled—i.e., stay out of their way.

The consultation didn't take too long and within a day or so, I was back in the helicopter, returning to Resolute Bay and my flight home (this time by scheduled airline). Looking back on that experience, I'm amazed how much money and time was spent getting me to the remote camp for a one-day consultation. But that's how things were done in those days before personal computers, the internet and WiFi made communication instant. Of course, being financed by petroleum companies helped make things happen.

Although the objective of my trip was to get to Ellef Ringnes, the definite highlight for me was the marine biology work and our personal discovery of the Franklin graves on Beechey Island—all the result of happenstance. Beechey Island was a small step back into history and helped me put my Arctic experiences into perspective. Over the three seasons, I had been brought to the Arctic to do work in the relative comfort of a bubble of technology and fossil energy that was unknown a scant 100 or so years ago. I was easily transported to where I needed to be and protected from the ravages of the weather by high tech clothing, modern camp structures and instant heat. Contrast this with the sacrifices and deprivation the European arctic explorers of the 19th century endured and you soon realize the importance of the foundation of knowledge these heroes provided for the research we do and the knowledge we gain today.

Slide 55 - Wrottesley Valley, Boothia Peninsula, 1975

On the other hand, my 1975 experiences camping with David Nanook opened my eyes to a culture that had long adapted to the extremes of cold, ice and snow. Building, sleeping and living in an igloo, even for just a few days, gave me new respect for the Inuit and what they have accomplished over the millennia. David also told me much about his life and the changes he was seeing as we Kabloona came in greater and greater numbers to exploit the resources below their feet.

Now, looking back from the perspective of the 21st century, the amount of fossil fuel we used to do our work in relative comfort and in pursuit of yet more fossil fuel boggles the mind. Of course, in the 1970s global warming was only discussed in small scientific circles. Today, we know better, but we seem unable to control the consumption of fossil fuels despite our knowledge of the damage we are doing, especially to people like the Inuit, who are seeing their land and lifestyle change forever. We need to do a lot more to plan for a future that respects all. Time is running out.