Death in the Woods

First Place, Magazine Feature Article

(Other)

Outdoor Writers of Canada

2012 National Communications Awards

(Sponsored by Shimano)

by Don Meredith © 2011

(first published in the May 2011 Alberta Outdoorsmen)

The coyote was not much more than a blur of fur skirting across the ski trail ahead, but the tail gave its identity away. I continued on my way stroking my ski poles into the deep, soft snow on either side of the well packed trail. Then a pair of ravens flew from the same place the coyote had come, followed by a pair of blue jays. What was I going to find at the top of this hill? Cautiously, I proceeded keeping an eye on the bush to the left of the trail.

As I arrived at the top, I saw the object of the birds’ and coyote’s interest. It was the separated hind leg of a deer hooked up in a barbed wire fence. Much of the meat on the leg had been eaten. There were many fresh tracks around the leg and a drag trail behind it. Then I became aware of the squawking of a large number of birds of various kinds further back in the bush. I assumed that’s where the kill site was and set out to find it.

That was easier said than done. This had been a particularly snowy winter and there was nearly a metre of snow on the ground. When I stepped off the trail I sank into snow almost to my hip. Following game trails I soon found myself floundering in thick bush that was rendering my skis useless. Realizing abandoning the skis would just make the situation worse, I gave up and returned home.

At least I had that choice. Unfortunately, our wildlife don’t. Ungulates (hoofed animals) have long legs and can handle most snow depths found in Alberta in “normal” years. However, this winter’s accumulation was definitely a challenge and our deer and other ungulates are suffering as a result. According to Dr. Margo Pybus, Provincial Wildlife Disease Specialist for the Fish and Wildlife Division, “we are seeing increased winter-related mortality throughout central Alberta and in the northwest.”

Even with long legs, walking through deep snow takes a lot more energy than with little or no snow on the ground. This is especially so if the snow has been sitting for a while and has been through a few freeze-thaw cycles causing crusted layers to form. Thus, when the snow depth gets close to the belly, deer tend to use the same trails over and over again. Deer are social animals and often go to feeding and bedding areas in groups. Sometimes these groups get quite large as more and more deer find the same well used paths and abandon other areas they would normally frequent but are now difficult to access. However, food in these “deer yards” soon becomes scarce, especially if the snow lasts long. As a result, hungry deer start looking for alternatives. Venturing out of the “yard” has many risks including not finding enough food to justify the energy expended and exposing oneself to predators while in vulnerable positions.

I’m guessing something like that happened to the hapless deer whose leg I found hanging on the fence. Perhaps it became too weak from starvation and got caught by a predator.

March and April can be especially harsh months under heavy snow conditions. Because it takes a lot of energy to walk and dig in deep snow, often what food is found does not compensate for the energy used. Fat stored in the summer and fall is depleting. Spring, with its fresh green sprouts and leaves, is still a few weeks off. It’s in late winter that pregnant does will lose their fetuses (through absorption or miscarriage) if they are not receiving enough nutrition. In extreme situations, starvation can step in, weakening the deer and further making them vulnerable to predation and disease.

This is also the time of year when deer and other ungulates will enter ranch and farm yards to feed on stored hay and grain, especially if they are starving. However, deer are browsers. Unlike cattle or elk which are grazers feeding on grasses like hay, deer normally eat protein-rich woody vegetation. Although they get some nutrition from hay and other grasses, the biota in their intestinal tracts that aids with digestion is not suited to completely break down grass. So, deer have been known to starve to death with full bellies in or near farm yards.

Moose

One hoofed animal that is especially well built for deep snow is the moose. It has large extra long legs supporting a powerful body that can step through most snow depths. That’s not to say they are invulnerable to deep snow conditions but they can better handle them.

Although moose are less vulnerable to deep snow than deer, they are more vulnerable to the winter tick (Dermacentor albipictus). As described in Dr. Bill Samuel’s excellent book, White as a Ghost, Winter Ticks and Moose (2004, Federation of Alberta Naturalists), this external parasite spends much of its life sucking the blood of moose, elk and white-tailed deer. However, tick infested moose suffer more than deer or elk. (The winter tick does not infest humans.)

As with most parasites, the life cycle of the winter tick is very interesting. Female ticks lay eggs in the leaf litter and duff on the ground in late May and early June. The eggs hatch in August and the six-legged larvae climb grasses or the limbs of shrubs and small trees to form aggregations of these “seed ticks” where they wait to grab onto a passing moose, elk or deer. The seed ticks infest their hosts from September to early November.

Once attached to the moose, the larva crawls through the fur to the skin where it inserts its sucking mouthparts and starts its first blood meal. By November the larva moults to become an eight-legged nymph. The nymph is dormant for a couple of months. Then in late January it starts taking blood meals again, and moults to the adult tick stage in February and March. The adults continue to feed on the moose.

The male ticks (about 6.5 mm long, dark brown with a white cross-hatch pattern on their backs) take only enough blood to produce sperm and then they move on to find females. The larger females (dark reddish-brown with no pattern on their backs) are less mobile at this time, taking a large blood meal to produce as many eggs as possible (increasing their size to about 15 mm). The ticks mate and then the females drop off the moose. The males stay on the moose to find more females but eventually drop off. Moose are tick-free from late May to August. The female ticks lay their eggs under fallen leaves in sheltered places, and the cycle is continued.

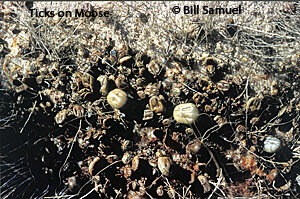

The problem for the moose is that they can be infested with many thousands of ticks at many times the densities normally found on elk or deer. In Elk Island National Park, for example, Dr. Samuel and his colleagues found on average 37,000 ticks on each moose (1.7 ticks per sq. cm), 1200 on elk (0.06/sq. cm) and 540 on white-tailed deer (0.05/sq. cm). But it gets worse for moose. Depending on the weather, moose density and other factors, individual moose can have as high as 100,000 or more ticks.

That’s quite a load, and it drives the moose to distraction. Instead of feeding or resting, heavily infested moose will spend more and more time grooming and scratching their hides against trees and other objects to ease the irritation. These actions rub fur off the hide and the moose start looking very pale or “ghostly.” As the winter drags on, heavily infested moose do not eat enough and begin to suffer from starvation. Calves are especially vulnerable, and more of them will die than adults. It is in March and April that country residents report finding exhausted, tick infested moose coming into yards to find feed or just rest because they’re too exhausted to continue the fight.

Fortunately, these large infestations don’t occur every year, and are associated with high moose densities among other factors. As of this writing (early April), Dr. Pybus reports that the Grande Prairie/Peace River and Athabasca regions are seeing tick-stressed moose. However, she points out that one of the benefits of deep snow packs in late winter is that female ticks dropping off moose into deep snow will die before they can deposit their eggs, reducing the rate of infestation the following fall.

It’s tough to see starving deer or exhausted moose suffering. However, Margo Pybus reminded me that many deer populations across the province have been increasing in recent years, threatening their habitat, damaging stored hay, grain and silage, and becoming hazards on highways. If other mortality factors, such as hunting, predation or disease don’t bring the populations back into balance with their habitats, starvation will. As a trapper told me several years ago, “Mother Nature is a cruel bitch.”